One Million Workers

When Liz Shuler declared that the AFL-CIO would add a million new workers to the labor movement, she likely expected a better reception.

Her declaration that the AFL-CIO would support affiliates in organizing a million new workers by the close of the decade was a rare moment where concrete targets were added to routine pronouncements of “organizing the unorganized.” Looking back over a decade of AFL-CIO Conventions, it seems organizing commitments were notably free of clear goals.

Hamilton Nolan blasted the goal as “continued decline,” while Steven Greenhouse quoted multiple labor leaders expressing skepticism that Shuler’s goal was enough. They’re correct — to a point. A million workers isn’t enough. But differences of opinion over the correct target obscures the bigger problem: how do we achieve any growth at all?

Growing the Movement

“We will develop, implement and scale powerful campaigns for unprecedented union growth. By concentrating resources and coordinating to achieve the biggest wins, the CTO will use the power of the entire U.S. labor movement. That’s 13 million of us in 57 unions in every state, in every ZIP code, in all industries. And here’s the bottom line. In the next 10 years, we will organize and grow our movement by more than 1 million working people.”

Is one million workers too easy?

Truly breaking down Shuler’s goal has been overlooked: she’s pledged to grow the movement by a million workers. A reasonable read of her remarks indicates that she intends there to be a million more union members, in absolute numbers, than exist right now. The remarks suggest she also intends those to be members of the AFL-CIO — so not inclusive of any members added to the NEA, SEIU, or Teamsters, the latter two of which are among the most institutionally aggressive organizers in organized labor.

That actually means organizing far more than a million new workers. Given changes in the structure of the American economy and the erosion of union membership (especially in legacy industries), labor can’t even organize at replacement levels, let alone levels that would add membership. There are currently three million fewer union members than there were in 1983, and unions have lost 581,000 members in the past three years alone, driven primarily by private sector losses. A million worker goal would require to both organize at replacement levels, plus levels sufficient to add a million new workers.

What does that entail? There are three main ways that labor adds membership: private sector organizing under the NLRB process, public sector organizing under state board processes, and organizing outside of those processes. (Note: this doesn’t encompass federal sector and railway organizing, both of which are limited in what they can add in absolute terms, or non-traditional “direct join” organizing like the Fight for $15.)

So how do we put Shuler’s goal in conversation with existing organizing activity? Let’s start with the NLRB.

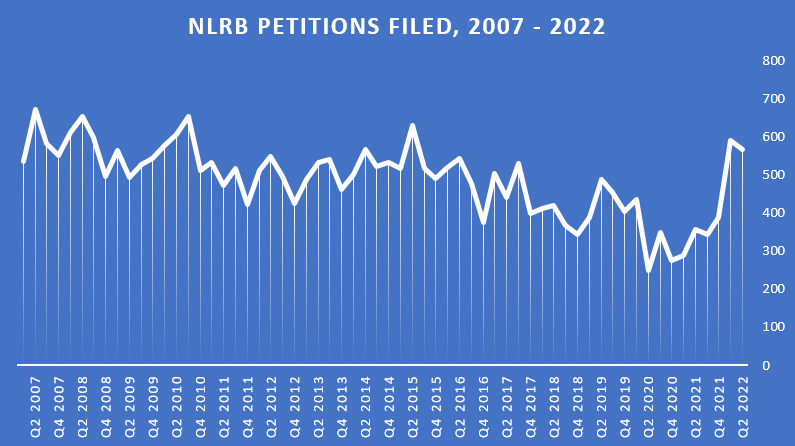

NLRB petitions are an imperfect measure at best; some of the most effective large-scale organizing happens outside of the NLRB process. But it’s an indicator of overall organizing activity, even if it’s far short of the whole picture. It’s a datapoint that gives us some sense of what organizing activity is occurring, and at what scale.

An analysis of NLRB filings by quarter shows that the recent surge in representation petitions is not, in absolute terms, a surge: it’s a surge from an abnormal low, back to levels more typical for the past fifteen years.

Although there’s an undeniable increase in numbers of NLRB election filings, it’s a surge to Obama-era levels of organizing: a level that was woefully insufficient to maintain levels of labor power and density, let alone increase it.

The inability to maintain numbers despite a seemingly high level of election activity is in part due to the scale of organizing. The average bargaining unit size ranges from 40 workers to 60 workers depending on the quarter; between Q1 2022 and Q2 2022, petitions involving just shy of 60,000 workers have been filed. If the pace held for the entire year (history suggests it will not), labor would need a win rate around 80% to hit 100,000 workers organized, which would be well short of the pace needed to hit Shuler’s goal — even without factoring in membership loss.

In short: for all of the union activity occurring at the moment, it will get us nowhere near Shuler’s goal.

The NLRB doesn’t include all organizing. Agreements outside of the Board process are rare but often result in some of the largest-scale organizing victories. Moreover, some of the largest recent victories have been public sector organizing, including a staggering victory in California organizing over 17,000 student researchers in the University of California system. But given the comparative levels of density and where the loss is occurring, it’s fair to assume that the majority of ground needs to be made up within the private sector — and that almost uniformly means workers subject to the NLRA.

Conclusion

In other words, Shuler’s quick critics probably spoke too soon.

A million workers isn’t enough. Adding that many new union members wouldn’t even increase union density by a full percentage point. We need more members, and we need them now — not by 2030.

But we could pledge to organize in greater numbers, and it wouldn’t mean a thing if we can’t even hit smaller targets. The difficulty labor faces reaching even a million new workers should be a wakeup call that almost nobody is organizing — not programmatically, at least — at the scale and pace necessary. At this stage, bickering over the number is irrelevant: asking and defining in clear, unromantic terms how we hit even a million is what needs to be done.

That makes the absence of Starbucks workers from the AFL-CIO Convention all the more striking, given that Workers United is possibly the only union programmatically embracing the sort of organizing necessary to hit or surpass Shuler’s goal. Staff-driven approaches simply cannot scale up adequately, no matter how many centers are created and how many dues dollars are thrown at the problem.

Workers, whether existing members or prospective members, need to be trusted to drive organizing and drive bargaining to a far greater degree than most unions — including some organizing-heavy unions — are comfortable. This isn’t a new or particularly revelatory insight. It’s a point embraced by the industrial unionists of the CIO in the 1930s, and largely abandoned by organized labor today.

We need to seize and push our momentum well past what we’re institutionally comfortable with: a point convincingly made by Chris Brooks in a feature piece for In These Times. How workers are winning might run contrary to our instincts. But if that’s true, our instincts, rather than their organizing, are what need to change.

Ultimately, bickering over whether our goal is a million workers or two million workers is largely irrelevant to the bigger question: how do we organize with an approach and scale necessary to add any workers to the ranks of labor?

New Writing

“How Unions Are Fighting To Protect Abortion Rights” in In These Times (6/8/22)

“Pennsylvania Portents” in The Baffler (5/20/22)

The grabbing hands grab all they can

All for themselves, after all

The grabbing hands grab all they can

All for themselves, after all

It's a competitive world

Everything counts in large amounts

Everything counts in large amounts

Everything counts in large amounts

— “Everything Counts,” Depeche Mode